OR IS IT??!?!?

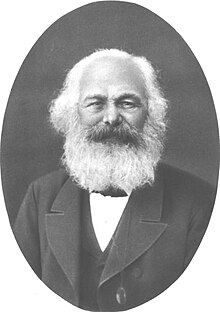

Among the classical economists, the mainstream theory was the labor theory of value. This idea was pushed by Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Marx.

Adam Smith David Ricardo Karl Marx

According to this theory, the value of a good is derived by the amount of labor required in obtaining it. Because of this, the value of that good is inherit. There is an objectively "correct" price.

The value of a commodity, or the quantity of any other commodity for which it will exchange, depends on the relative quantity of labour which is necessary for its production, and not as the greater or less compensation which is paid for that labour.

- David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Chapter 1Karl Marx play an interesting role here, actually. By his thinking, if all value comes from labor, then any "capitalist" who makes a profit must do so by denying the laborer the full value of their output. Hence, all profit is exploitation. The labor theory of value is key to most, if not all, of his school of thought.

Of course, his theory of value is a bit unique as he's declaring for abolishing private property.

This theory was so widely accepted because of something known as the Diamond-Water Paradox. Why is it that water, something absolutely vital for human life, has such a low price while diamonds, which certainly don't serve as a basic human necessity, demand such a high price? The answer Adam Smith had come up with is that water is just a lot easier to get. It does not require anywhere near as much labor, so it has a lower price. Diamonds, however, require a lot of work both collecting and refining it, so it has a higher price.

The real price of every thing, what every thing really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it.

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Chapter 5

The labor theory of value wasn't universally accepted though, even in the days of Adam Smith. Frédéric Bastiat, the inventor of the Broken Window Fallacy, took particular problems with it. After all, wouldn't this mean that sources of difficulty actually make work more valuable? Bastiat pointed out the absurdity of this notion in his book Economic Harmonies.

It is too bad that Robinson Crusoe has invented nets to catch fish or game; for it lessens by that much the efforts he exerts for a given result; he is less rich.

...

It would be too completely evident that wealth does not consist in the amount of effort required for each satisfaction obtained, but that the exact opposite is true. We should understand that value does not consist in the want or the obstacle or the effort, but in the satisfaction; and we should readily admit that although Robinson Crusoe is both producer and consumer, in order to gauge his progress, we must look, not at his labor, but at its results.

- Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies, Chapter 4, emphasis added

The idea of value being presented here is the subjective theory of value. It states that value is not inherit to a good, but is derived from the value that man gives to the world around him. His value is derived from the relative ends a man is trying to fulfill.

However, Bastiat was unable to come up with a coherent explanation for the diamond-water paradox. After all, if this is true, why do we pay so little for drinking water? Are we honestly supposed to believe that people value having a diamond less than drinking?

Because of this, the subjective theory of value was not really accepted into mainstream economic thinking until the end of the 19th century, when it was discovered independently and nearly simultaneously by William Stanley Jevons, Léon Walras, and Carl Menger, the last of which founded the Austrian School of Economics. These men developed the concept of marginal utility.

Carl Menger and his magnificent beard.

Essentially, this insight showed that people are never in the position to judge a good by its class. You are never in a position to ask whether you would rather own all the diamonds in the world or all the water in the world. If you were, I doubt the diamond-water paradox would arise! Instead, people are trading discrete quantities of goods.

Imagine that I offer you a cup of diamonds for a cup of water. If you are like most people, you would accept this trade. But when you make this trade, you are not giving up drinking. Instead, you are giving up whatever end you would have fulfilled if you had another cup of water, which might be something frivolous like watering one of your plants again. This concept of what you could have done with this extra unit is known as an opportunity cost. This cost is the true cost of every exchange you ever make.

This theory also works well because it explains how trade works. If the value of things are intrinsic, then what would be the point of trading something of equal value? I'll trade you this dollar bill for your dollar bill. According to the Austrian School, a person's action shows their scale of values, or an imaginary scale by which they value one thing over another. If I buy milk at the store for $1.00, then that shows that having milk is higher on my scale of values than having $1. I "win" the trade. At the same time, the person selling the milk shows that having $1 is higher on his scale of value than having milk. He "wins" the trade. Each person comes off more satisfied and richer than before. If value was inherit, each person coming out of a trade with a more valuable thing makes about as much sense as each person coming off with the heavier object.

There should also be a note that this idea of subjective values is in no way trying to make a moral or philosophical statement. There might be some divine being out there that sets an official scale of values, such as a moral doctrine, that can accurately be called an objective standard of value. There might be some "perfect form", like Plato suggested, of beauty. One might argue that there is an intrinsic value to human life.

Economics and praxeology does not deal with such matters though, but only with how people act. If person A murders person B, we can accurately say that to his standard of values, person A preferred person B to being dead rather than him being alive. From the scientific standpoint, we cannot say whether this action is moral or not. To him, this human's life was obviously not considered intrinsically valuable.

This concept blew apart any previous idea of value, and was so influential that it's discovery is known as the Marginal Revolution. It forever changed the approach of economics as if it were a natural science, existing on its own, to something entirely dependent on people's own values, that can never be fully understood. To properly understand economics, we must understand the motivations of an acting man, not of something intrinsic to the world.

LOL, kidding, that would be retarded. Economics is a science, and those head government scientists properly know how to run the country and can control and manipulate it so it does exactly the right thing. Only those crazy Austrian Economists still think crazy things like that. Trust your leaders. They have very complicated charts and graphs, after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment